This is article one in the Educational Business Series (EBS).

Introduction

Accounting topics commonly align with one or more of the three accounting classes: financial accounting; managerial accounting; and financial management.

Financial accounting addresses the recording and reporting of financial transactions and the preparation of financial statements (e.g., income statement, balance sheet, cash flow statement, etc.) for the benefit of an entity and external stakeholders such as investors, creditors, regulators, and tax authorities. It adheres to standardized frameworks such as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) in the United States or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) globally (Kieso, et al, 2016).

Managerial accounting is “the provision of accounting information for a company’s internal users. More specifically, managerial accounting represents the firm’s internal accounting system designed to provide the necessary financial and non-financial information that helps company managers make the best possible decisions” (Mowen et al, 2018, p. 4). This involves “the process of collecting, analyzing, interpreting, and presenting financial and non-financial information to assist management in decision-making, planning, and control within an organization. Unlike financial accounting, which focuses on preparing standardized financial statements for external stakeholders, managerial accounting is internally focused and provides tailored information to support strategic and operational decisions” (xAI, Grok 4, 2025).

Financial management focuses on “strategic planning, organizing, directing, and controlling financial activities within an organization to achieve specific financial objectives. It involves the efficient and effective management of monetary resources to maximize value, ensure liquidity, and mitigate risks. Financial management encompasses a range of activities, including budgeting, forecasting, investment decisions, risk management, and the oversight of financial operations” (xAI, Grok 4, 2025).

This article introduces financial accounting.

Reader’s note: A finance calculator https://www.calculator.net/finance-calculator.html and financial calculators https://www.calculator.net/financial-calculator.html are available at calculator.net.

Reader’s note: If you are brand new to the topic of accounting; it is recommended that you read a brief, easy-to-understand introductory book titled “Accounting Made Simple” by Mike Piper, CPA.

History

Financial accounting can be traced as far back as ancient Mesopotamia around 7000 BC where clay tokens and tablets were used to record transactions, facilitate trade, and aid in taxation involving goods. By 3000 BC, Egypt was using basic debit-credit accounting principles.

In the Roman Empire, a more formalized system of accounting emerged through the use of the codex accepti et expensi, a ledger system that separated cash receipts (accepti) from payments (expensi).

However, it was not until the late 13th century that the Italian mathematician Luca Pacioli (the “father of accounting”) codified double-entry bookkeeping in his 1494 treatise Summa de Arithmetica, Geometria, Proportioni et Proportionalita.

The Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries brought accrual accounting to match revenues with expenses over time, departing from cash-based methods, and accounting bodies were formed such as the Society of Accountants in Edinburgh (1854) and the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (1880). Legal mandates, such as the U.K. Companies Acts of 1844 and 1862, began to require financial statements for auditing purposes.

In 1939, the American Institute of Accountants (now AICPA) endorsed Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and in 1973 the International Accounting Standards Committee (now the International Accounting Standards Board [IASB]) issued International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) which are presently adopted by over 140 countries.

More recently, financial accounting has integrated with enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, blockchain for immutable ledgers, and artificial intelligence for predictive analytics (xAI, Grok 4, 2025).

Assumptions and Principles

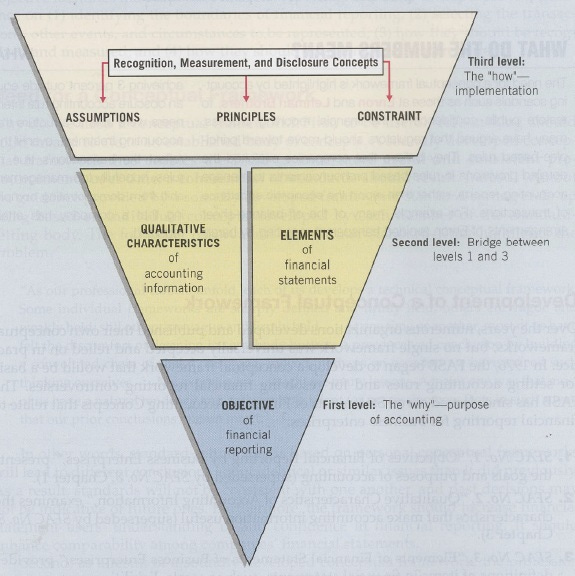

Accounting incorporates assumptions from which principles are derived.

Examples of assumptions include: 1. the economic entity assumption (the business is treated as a separate distinct entity); 2. the going concern assumption (the business will exist for a long time); 3. the monetary unit assumption (money is the common denominator of all business activity); and 4. the periodicity assumption (businesses report activities by time periods).

Examples of principles include: 1. the historical cost principle (the value of an asset is the cost of an asset); 2. the revenue recognition principle (revenues are recorded on the date that goods or services are transferred, not actually received); 3. the matching principle (expenses are recorded in the same time period as the revenues they help to generate); and 4. the full disclosure principle (financial statements must include any information that has a significant effect [past, present, or future] on the financial status of the business).

The assumptions and principles listed are part of a standardized framework of accounting rules, standards, and procedures that companies in the United States must follow when preparing and reporting their financial statements named Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Note that outside of the United States, the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) is commonly used.

The Accounting Equation

It is customary to start accounting introductions with the accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Owner’s Equity.

“Assets: Resources owned or controlled by the entity that have probable future economic benefits (e.g., cash, accounts receivable, inventory, property, plant, and equipment).

Liabilities: Present obligations of the entity arising from past events, the settlement of which is expected to result in an outflow of resources embodying economic benefits (e.g., accounts payable, loans, accrued expenses).

Equity (also called Owners’ Equity, Shareholders’ Equity, or Net Assets): The residual interest in the assets of the entity after deducting all its liabilities. It represents the owners’ claims on the business and includes contributed capital, retained earnings, and other reserves.retained earnings, and other reserves.

This equation must always remain in balance after every transaction, forming the foundation of double-entry bookkeeping. Every debit has a corresponding credit that affects the equation in a way that preserves equality. The balance sheet is simply a detailed presentation of this equation at a specific point in time.

This relationship is the cornerstone of financial accounting and ensures that the financial position of an entity is accurately represented.” (xAI, Grok 4, 2025).

Financial Statements

Financial statements consist of ten elements that show the amounts, claims, and changes to an organization’s resources. They are: assets, liabilities, equity, revenues, expenses, gains, losses, comprehensive income, investment by owners, and distributions to owners.

Under GAAP and IFRS, there are four basic financial statements of a business for which each serves a distinct purpose in presenting the financial position, performance, and cash flows of the business.

“1. Balance Sheet (Statement of Financial Position): Provides a snapshot of the company’s financial position at a specific point in time (usually the end of a reporting period).

Key components:

a. Assets (what the company owns)

b. Liabilities (what the company owes)

c. Equity (owners’ residual interest: Assets − Liabilities)

It answers the question: “What resources does the company control, how are they financed, and what is the net worth at this moment?”

2. Income Statement (Statement of Profit or Loss / Comprehensive Income): Measures the company’s financial performance over a period of time (e.g., month, quarter, year) by showing revenues earned, expenses incurred, and the resulting profit or loss.

Key components:

a. Revenue/Sales

b. Cost of sales and operating expenses

c. Other income/expenses, taxes, and non-controlling interests

d. Net income (or loss)

It answers the question: “How profitable was the business during the period?”

3. Cash Flow Statement (Statement of Cash Flows): Explains the change in cash and cash equivalents during the period by classifying cash movements into three main activities.

Key sections:

a. Operating activities (cash generated or used by core business operations)

b. Investing activities (cash used or received from purchases/sales of long-term assets and investments)

c. Financing activities (cash from issuing or repaying debt, equity transactions, and dividends)

It answers the question: “Where did cash come from and how was it used during the period?” This is critical because profitability (income statement) does not necessarily equal cash generation.

4. Statement of Changes in Equity (Statement of Owners’ Equity or Statement of Retained Earnings): Reconciles the opening and closing balances of equity accounts over the period, showing how net income, dividends, share issuances/repurchases, and other comprehensive income items affect owners’ equity.

Key components:

a. Beginning equity balance

b. Net income (or loss) transferred from the income statement

c. Dividends or distributions

d. Issuance or repurchase of shares

e. Other comprehensive income (e.g., revaluation gains, foreign currency translation)

f. Ending equity balance

It answers the question: “How did the owners’ stake in the company change during the period?”

In addition, IFRS or certain GAAP requirements include Notes to the Financial Statements and, where applicable, a Statement of Comprehensive Income. The notes are an integral part of the financial statements, providing detailed explanations, accounting policies, and additional disclosures necessary for a fair understanding of the four primary statements.

Together, these statements provide a complete, interrelated picture of a business’s financial health, performance, liquidity, and solvency, enabling stakeholders (investors, creditors, management, regulators) to make informed economic decisions” (xAI, Grok 4, 2025).

Financial statements are typically produced in the following order: 1. Income Statement (shows total revenues, expenses, and resulting net income for a given period of time); 2. Statement of Changes in Equity (shows the beginning capital for the period, plus any investments and withdrawals); Balance Sheet (provides a snapshot of the company’s financial position [assets, liabilities, equity] at a specific point in time); and 4. Cash Flow Statement (explains the change in cash and cash equivalents during the period).

And, financial statements for a particular business will follow the accounting period that it has chosen. This may either be a fiscal year or a calendar year. A fiscal year is a 12-month accounting period chosen that may begin on any date. A calendar year is a 12-month accounting period that runs from January 1 to December 31.

Business Entities

Business entities are typically either a sole proprietorship, a partnership, or a corporation. A sole proprietorship is owned by a single person; a partnership is owned by more than one person; and a corporation (e.g. C corporation, S corporation, limited liability corporation, etc.) is owned by its shareholders (people who own shares of stock in the corporation).

Owner’s equity appears on financial statements per the type of business entity. For example, a corporation will use a statement of retained earnings that will reflect issues such as dividends rather than a statement of owner’s equity.

Merchandising Businesses Versus Service Businesses

“The fundamental accounting distinction arises from the presence or absence of merchandise inventory. Merchandising entities must track the cost of inventory purchased and sold, giving rise to the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) account and the concept of gross profit.

This requires detailed inventory records and a multi-step income statement. Service entities, by contrast, have little or no inventory of goods for resale; their primary cost is labor and overhead directly tied to delivering the service.

Consequently, service entity accounting is simpler as there is no Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) calculation, no inventory valuation issues (first-in-first-out FIFO, last-in-first-out LIFO, etc.), and typically a single-step income statement that subtracts all operating expenses directly from service revenue.

These structural differences affect financial ratios (e.g., inventory turnover, gross margin percentage), tax considerations, and internal management reporting, making merchandising accounting more inventory-centric while service accounting focuses predominantly on labor and overhead cost control” (xAI, Grok 4, 2025).

Cash Basis versus Accrual Basis

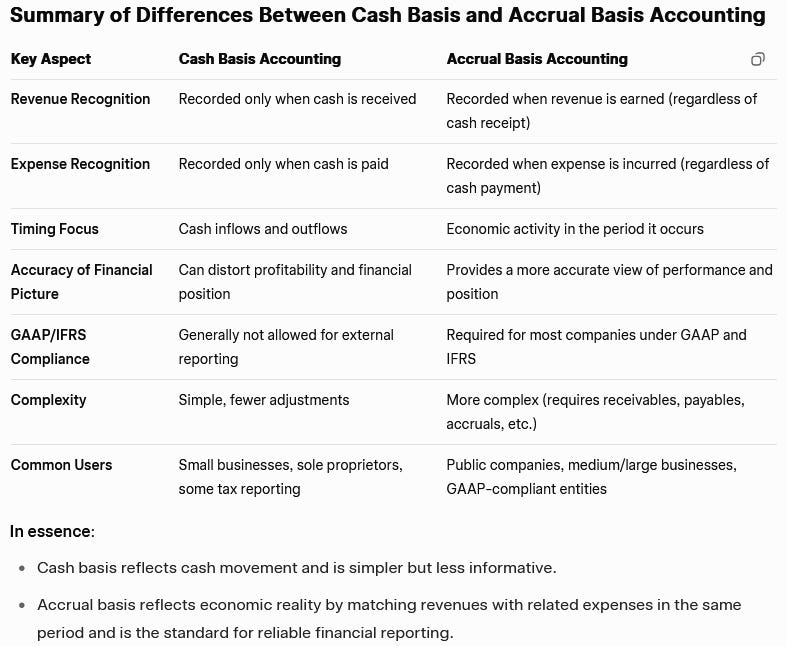

Cash Basis Accounting is an accounting method in which revenues and expenses are recognized and recorded only when cash actually changes hands.

Accrual Basis Accounting is the accounting method required by Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) in which revenues and expenses are recognized and recorded when they are earned or incurred, regardless of when cash is actually received or paid.

1. Cash basis is cash-flow oriented and simpler, but it can misrepresent economic reality over multiple periods.

2. Accrual basis follows the matching principle (revenues matched with the expenses incurred to generate them) and is considered the more accurate method for assessing long-term profitability and financial position, which is why it is mandated for most external financial statements.

The Accounting Cycle

Most companies perform a series of steps that make up the accounting cycle.

“The accounting cycle is a systematic, standardized process that organizations use to record, classify, and summarize financial transactions during a specific accounting period (typically a month, quarter, or year) and to prepare accurate financial statements. It ensures that all economic events are properly captured and reported in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) or International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).

The accounting cycle consists of the following steps, performed in sequence:

I. Identify, Analyze, and Record Transactions:

1. Review source documents (invoices, receipts, contracts, etc.) to determine which events qualify as accounting transactions and affect the financial position of the entity.

2. Record Journal Entries (Journalizing)

3. Enter the transactions in chronological order in the general journal using double-entry accounting (debits must equal credits).

4. Post to the General Ledger

5. Transfer the journal entries to the appropriate T-accounts in the general ledger, updating each account’s balance.

6. Prepare an Unadjusted Trial Balance

7. List all ledger account balances at the end of the period to verify that total debits equal total credits before any adjustments.

8. Record Adjusting Entries

9. Make necessary accrual-basis adjustments at the end of the period for items such as:

a. Accrued revenues and expenses

b. Prepaid expenses (e.g., insurance, rent)

c. Unearned (deferred) revenues

d. Depreciation and amortization

e. Allowance for doubtful accounts

II. Prepare an Adjusted Trial Balance:

1. Compile an updated trial balance that incorporates the adjusting entries to confirm arithmetic accuracy after adjustments.

III. Prepare Financial Statements:

1. From the adjusted trial balance, produce the four primary financial statements (in the following usual order):

a. Income Statement (Profit & Loss)

b. Statement of Comprehensive Income (if applicable)

c. Statement of Changes in Equity

d. Balance Sheet (Statement of Financial Position)

e. Cash Flow Statement

III. Record Closing Entries:

1. Close temporary (nominal) accounts—revenues, expenses, gains, losses, and dividends/withdrawals—to Retained Earnings (or the appropriate equity account) so that these accounts begin the next period with zero balances.

2. Prepare a Post-Closing Trial Balance

3. Verify that only permanent (real) accounts (assets, liabilities, and equity) remain with balances and that debits still equal credits. This serves as the starting point for the next accounting period.

After the post-closing trial balance is confirmed, the cycle repeats for the subsequent period. In many modern systems using accounting software, steps 2 through 6 are largely automated, but the conceptual sequence and the need for adjusting and closing entries remain essential for accurate financial reporting. This structured process maintains the integrity of financial records and enables stakeholders to rely on timely, accurate, and comparable financial statements” (xAI, Grok 4, 2025).

To summarize; a business will identify the information that needs to be tracked which is typically contained in source documents (such as invoices, etc.). The source documents are analyzed to determine how they will be recorded in the accounting system and then recorded in the required journals and the general ledger. Afterwards, a trial balance is generated to ensure the total amount of debits equal the total amount of credits.

In accrual basis accounting, adjusting entries are performed as necessary to ensure that all revenues and expenses generated during the accounting period have been correctly recorded. After all adjusting entries are recorded, an adjusted trial balance is prepared and financial statements are produced.

Finally, revenue and expense accounts must be “closed” so that these accounts begin with a zero balance at the beginning of the next accounting period. This is accomplished by recording closing entries and generating a post-closing trial balance (to verify that debits equal credits). The ledger will then be ready for recording transactions for the next accounting period.

Financial Ratios

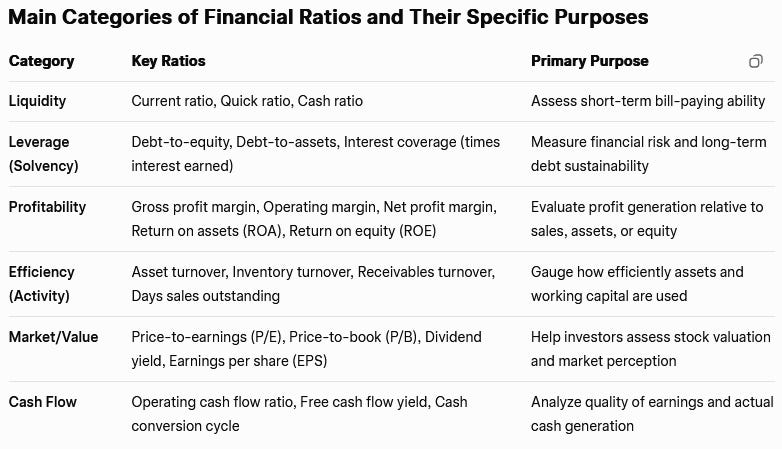

At this point, it is time to introduce financial ratios. “Financial ratios are calculated from items appearing on a company’s financial statements (balance sheet, income statement, and cash flow statement) to evaluate various aspects of its operating performance, financial health, and value. They are widely used by internal management, investors, creditors, analysts, and regulators for the following key purposes:

1. Performance Evaluation: ratios measure how effectively a company is generating profits and utilizing its assets. They allow management and stakeholders to assess operational efficiency and profitability trends over time or against industry peers.

2. Financial Health and Risk Assessment: they reveal the company’s solvency (ability to meet long-term obligations), liquidity (ability to meet short-term obligations), and overall financial stability. Creditors and bond rating agencies rely heavily on these ratios when deciding whether to extend credit or at what interest rate.

3. Investment Decision Making: investors and equity analysts use valuation and profitability ratios to determine whether a stock is overvalued, undervalued, or fairly priced relative to earnings, cash flow, assets, or peers.

4. Credit Analysis and Lending Decisions: banks and other lenders examine liquidity, leverage, and coverage ratios to assess default risk and set loan covenants (e.g., requiring the borrower to maintain a minimum current ratio or maximum debt-to-equity ratio).

5. Benchmarking and Peer Comparison: ratios standardize financial data so companies of different sizes can be compared directly. Industry averages and competitor ratios serve as benchmarks to identify relative strengths and weaknesses.

6. Trend Analysis and Forecasting: by tracking ratios over multiple periods, users can identify improving or deteriorating trends and project future performance.

7. Management Control and Strategic Planning: internal managers set targets for key ratios (e.g., return on assets, inventory turnover) and use them in budgeting, incentive compensation plans, and operational improvement initiatives” (xAI, Grok 4, 2025).

Reader’s note: The Corporate Finance Institute provides a free downloadable “Financial Ratios ebook” to peruse the most commonly used financial ratios: https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/assets/CFI-Financial-Ratios-Cheat-Sheet-eBook.pdf

Conclusion

Financial accounting is the branch of accounting that focuses on the systematic recording, summarization, and reporting of an entity’s financial transactions and economic events in accordance with established standards ensuring transparent, standardized, and verifiable financial reporting that enables assessment of the financial and economic health and performance of an organization.

As this is but an introduction; a recent edition of Kieso, et al’s Intermediate Accounting is suggested for expanded content while a recent edition of Schaum’s Outline of Financial Accounting (with answers) is recommended to work through financial accounting problems for competency.

Bibliography:

Benedict, A., & Elliott, B. (2011). Financial accounting: an introduction (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Britton, A., & Waterston, C. (2006). Financial accounting (4th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Individual Software Inc. (2023). Professor Teaches QuickBooks 2023 Tutorial Set - Interactive Training for Intuit’s Quickbooks versions 2023, 2022 and 2021, Accounting Fundamentals and Business planning. Individual Software, Inc. [Computer Software]. https://www.individualsoftware.com/product/professor-teaches-quickbooks-2023/

Kieso, D. E., Weygandt, J. J., & Warfield, T. D. (2016). Intermediate Accounting (16th ed). Wiley.

Mostyn, G. (2017). Basic accounting concepts, principles, and procedures (2nd ed.), volume 1. Worthy and James Publishing.

Mostyn, G. (2017). Basic accounting concepts, principles and procedures (2nd ed.), volume 2. Worthy and James Publishing.

Phillips, F., Libby R., Libby, P. A., & Mackintosh, B. (2015). Fundamentals of financial accounting (4th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Piper, M. (2008). Accounting made simple. Simple Subjects, LLC.

Rich, J. S., Jones, J. P., Mowen, M. M., & Hansen D. R. (2010). Cornerstones of financial accounting. Cengage.

Shim, J. K., & Siegel, J. G. (2011). Schaum’s outline of financial accounting (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Stickney, C. P., Brown, P. R., & Wahlen, J. M. (2007). Financial reporting, financial statement analysis, and valuation: a strategic perspective (6th ed.). Thomson.

Weygandt, J. J., Kimmel, P. D., & Kieso, D. E. (2019). Financial accounting with international financial reporting standards (4th ed.). Wiley.

Wild, J., Shaw, K., & Chiappetta, B. (2016). Fundamental accounting principles (23rd ed.). McGraw Hill.

xAI. (2025). Grok (version 4). https://grok.com/

Fair Use: Copyright Disclaimer Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act in 1976; Allowance is made for “Fair Use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statue that might otherwise be infringing. All rights and credit go directly to its rightful owners. No copyright infringement intended.

Copyright © 2025 Paul L. Pothier. All rights reserved.