This is article two in the Educational Business Series (EBS).

Introduction and History

Robbins (2005) defines organizational behavior (OB) as:

“a field of study that investigates the impact that individuals, groups, and structure have on behavior within organizations for the purpose of applying such knowledge toward improving an organization’s effectiveness” (p. 9).

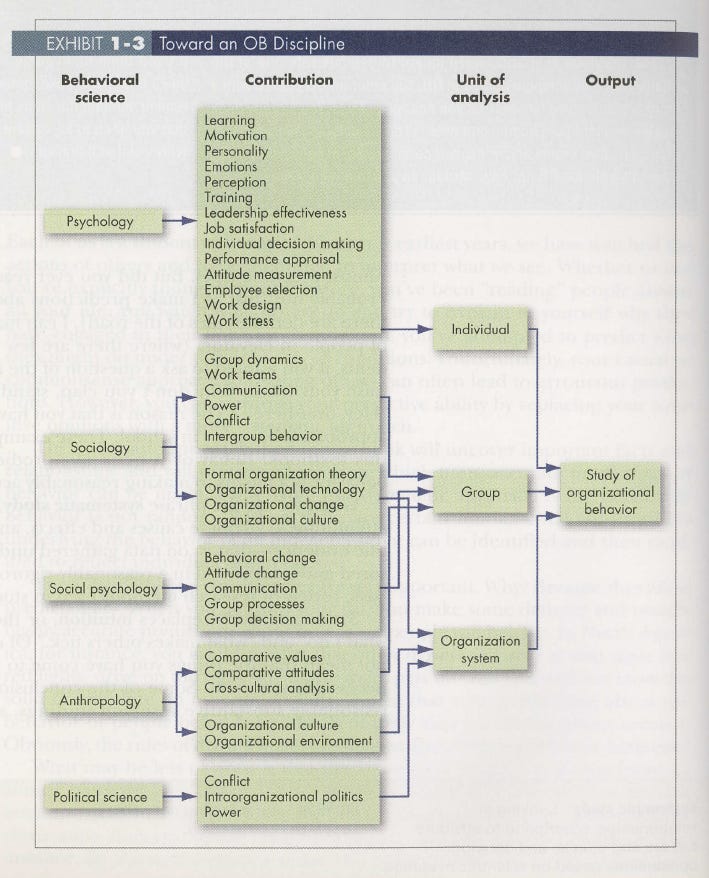

OB is a field of study, which means it is a distinct area of expertise with a common body of knowledge. OB targets three determinants of behavior within organizations which are individuals (micro-level), groups (mesa-level), and structure (macro-level) which it examines using the methods of other academic disciplines. Of course, the output of organizational behavior studies, which finds application in organizations, reflects these contributions (inputs) from other academic disciplines. Inputs affect output.

Whenever people interact in organizations, many factors come into play. Organizational studies attempt to understand and model these factors. Like all social sciences, OB seeks to control, predict, and explain. The field of study is concerned with what people do in an organization, how what they do affects the organization, and how the organization might respond to realize better outcomes.

OB is a large subject that isn’t easily communicated in a linear manner. Most guides on the topic are extensive. While the roots of organizational theory can be traced back to antiquity, organizational studies are generally considered to have begun as an academic discipline with the scientific management of the 1890s. Subsequently, research was turned into business practices.

One of the first people to capture on paper the processes and practices of organizations was Henri Fayol (1841-1925). A mining engineer and manager by profession, Fayol defined the nature and working patterns of late nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century organization in his 1909 book titled L'exposee des principles generaux d'administration (i.e. General and Industrial Management). In it, he laid down what he called the 14 principles of management.

Fayol’s 14 principles are: division of work; authority and responsibility; discipline; unity of command; unity of direction; subordination of individual interest; remuneration; centralization; scalar chain; order; equity; stability; initiative; and esprit de corps. He considered these principles essential for prediction, planning, decision-making, process management, control and coordination.

In 1911, Frederick Taylor (1856-1915) published the first edition of The Principles of Scientific Management. Proponents of scientific management believed that rationalizing the organization with precise sets of instructions and time-motion studies would lead to increased productivity and studies of different compensation systems were carried out. He stressed “science, not rule of thumb; harmony, not discord; cooperation, not individualism; maximum output, in place of restricted output; [and] the development of each man to his greatest efficiency and prosperity” (Taylor, 1919, p. 140).

Taylorism represented the peak of this movement which sought to secure the maximum prosperity for both employers and employees using scientific management principles; a focus that would have been a welcome change to the real wage stagnation, underemployment, labor force displacement, etc. that has been a problem for many U.S. private-sector workers in the years leading up to 2025 that resulted from non-symbiotic labor exploitation to maximize shareholder wealth. Mass offshoring of domestic jobs to foreign nations, mass outsourcing of domestic work to foreign firms, the mass importation of foreign labor, machinations of oligarchy and a slide toward plutocracy from hard lobbying, etc. were all utilized. (This was especially hard on U.S. citizens suffering from physical health issues that still needed sustainable work but were deemed unfit and easily replaced due to the manipulated domestic labor demand vs labor supply and unfair trade environment that largely prevented capitalistic-driven domestic solutions from manifesting to provide them accommodation). As this topic runs outside of the scope of this article, it needs to be addressed in greater depth in a future dedicated article which should also detail areas such as the new accelerating trend of replacing workers with AI automation.

Another pioneer was Max Weber (1864-1920) with his posthumous 1921 seminal publication titled Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. As one of the founders of sociology, Weber employed the discipline to construct a comparative methodology that articulated rational action in different contexts with a focus on bureaucracy.

After World War I, organizational studies began to analyze how human factors and psychology affected organizations (i.e. the Hawthorne Effect). This human relations movement focused more on teams, motivation, and the actualization of the goals of individuals within organizations however. Some of the more prominent early scholars included: Chester Barnard, Henri Fayol, Mary Parker, Follett, Frederick Herzberg, Abraham Maslow, David McClelland, and Victor Vroom.

The Second World War brought further changes and the invention of large-scale logistics and operations research led to a renewed interest in systems and rationalistic approaches to the study of organizations. Then in the 1960s and 1970s, the field was strongly influenced by social psychology and the emphasis in academic study was on quantitative research. Starting in the 1980s, cultural explanations of organizations and change became an important part of study. Qualitative methods of study became more acceptable, informed by anthropology and sociology.

Today, OB organizational studies departments are within business schools and industrial psychology and industrial economics programs. Some central areas of studies include how certain phenomena manifest in organizational settings. It is also important to note the role OB plays globally, including how OB is employed to normalize interactions between parties from diverse backgrounds with different cultural values.

Models, Theories, and Types

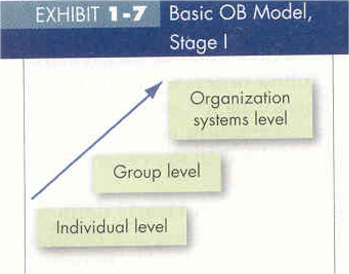

Robbins (2005) defines a model as “an abstraction of reality, a simplified representation of some real-world phenomenon” (p. 26). Models, also frequently referred to as theories [the two terms are used interchangeably], serve the useful purpose of systematically frame working understanding in attempting to describe systematically interrelated concepts or hypotheses that claims to explain and predict phenomena. A basic OB model consists of three levels analogous to building blocks. Each level builds on top of the level beneath it. Group concepts grow out of the individual foundation and organization systems grow from group concepts as Robbins demonstrates in Exhibit 1-7 on page 26.

There are many theories in OB including theories to describe what motivates people, effective leadership styles, conflict resolution, power acquisition, etc. Wood (1996) offers a very useful model for exploring behavioral events. He suggests that different levels of analysis can be applied when examining the significance of an organizational issue. He proposes eight, namely: individual, team, inter-group, organizational, inter-organizational, societal, international, and global.

Robbins (2005) states that, “In some cases, we have half a dozen or more separate theories that purport to explain and predict a given phenomenon” (p. 588). Interestingly, each reflects science at work. Theories attempting to explain common phenomena only show that the discipline of OB is growing and evolving.

The Manager and Organizational Behavior

To managers, OB is not just of theoretical interest, the discipline underpins practical organizational activities. For example, a discussion with an under-performing team member requires an understanding of individual motivation; running an effective meeting requires an appreciation of group dynamics, dealing with colleagues, and suppliers; customers from another country call to discuss a matter of cultural difference; helping two team members resolve a difference involves conflict resolution and negotiation skills; and so on.

Let us use a quick example. Say there was a new member of your team at work who attended the corporate induction program, but who is under performing? How might you account for their lower-than-expected level of performance? Depending on how you viewed that individual and who you listened to, here are some reasons you might come up with:

1. They just do not have the ability for the job (Individual level).

2. Their colleagues are not being supportive (Team level).

3. The induction program prepared by the Training department was of poor quality on this occasion (Intergroup level).

4. The company's training budget has been slashed (Organizational level).

And so on, the point being that the level of explanation chosen determines a view of the causes of the problem and affects the actions taken and solutions employed to solve it.

Inappropriate intervention at the wrong level can make a problem worse rather than better. Robbins (2005) states that decision making occurs as a reaction to a problem” and that “every decision requires the interpretation and evaluation of information” (p. 143). Consider the following in that light:

1. People tend to pick their favorite level of analysis to explain events, and then behave accordingly. This is often particularly true of external consultants brought into perform a "quick fix."

2. People are most familiar with, and often prefer, explanations at the individual level of behavior. Trying to change people by sending them on a training course is simpler than changing structures or upgrading technology. However, such explanations are often too simplistic, inaccurate, or incomplete.

3. As a general principle, any organizational problem can be usefully analyzed at ever-higher levels of abstraction. By considering a problem progressively at the individual, group, intergroup, and organizational levels, a deeper understanding of its causes can be gained. As a result, the tools needed to tackle the problem can be chosen more accurately, and applied more effectively.

Therefore, looking at a problem systematically will always yield a better understanding than simply leaping in with fixed preconceptions. OB is characterized by a view that organizations can be best explored by approaching them from a range of different perspectives. Just as there is no one best way to run and organize a business, so there is no one best perspective from which a total understanding of organizations can be gained; however, OB draws its strength from these rich and various perspectives seeking to detect which approach is most effective for a particular organization on a particular issue. Making the right OB choice yields positive results.

There are a number of factors that can affect an organization’s performance. These include:

1. The formal statements of philosophy, values, charter, and credo.

2. The behavior modeled by management.

3. The criteria used for reward, status, selection, promotion, and termination.

4. The stories, legends, myths, and parables about key people and events.

5. What leaders pay attention to, measure, and control.

6. Leaders’ reactions to critical incidents and crises that threaten.

7. Survival, challenge norms, and test values.

8. How the organization is designed and structured.

9. Organizational systems and procedures; and the competitive marketplace.

It is how organizations manage these elements during periods of transition that often seems to determine whether they achieve their goals.

Take Dell Computer Corporation, for example. They are one of the computer industry's biggest success stories and have successfully transitioned through the Internet paradigm. Dell was quick to take advantage of the Internet and technology and do it in a customer orientated manner. This resulted in a greater market share, much of it at the expense of competitors (see Compaq). Dell focused on the customer while maintaining a healthy sense of urgency and crisis. They were opportunistic, customer-focused, and rapid.

Their customer focus linked to strategic savvy, an ongoing commitment to innovation, and speed. To accomplish this required a commitment to internal organizational processes. A healthy, competitive culture where people partner through shared objectives and a common strategy emerged in the organization. They summed up their approach as follows:

1. Mobilize your people around a common goal.

2. Invest in long-term goals by hiring ahead of the game and communicating this commitment to your people.

3. Don't leave the talent search to the human resources section.

4. Cultivate a commitment to personal growth.

5. Build an infrastructure that rewards mastery.

6. Keep in touch with people at all levels of the company.

An example of a company that did not navigate the future well was Encyclopedia Britannica's loss of market share to Microsoft's Encarta (itself discontinued since 2009).

Loyalty surveys have shown that there is often more variation within organizations than between them highlighting that there can be both poorly-engaged and well-engaged groups within an organization. Top management may not even be aware who in their company is effectively engaging and who is not.

There are further key themes that seem to echo through companies that are successful and navigate the future well. Robbins (2005) includes:

1. Companies mirror their founders. Organizations start with founders and entrepreneurs whose personal assumptions and values gradually create a certain way of thinking and operating, and if their companies are successful, those ways of thinking and operating come to be taken for granted as the ‘‘right’’ way to run a business.

2. It is usually crisis, not periods of comfort, that propel significant cultural change. When all is going well for a business, changing the formula is often the last thing on anybody’s mind.

3. Achieving business success requires a sense of purpose first and good management practices.

4. Organizations achieve success in very different ways and by focusing on what is most important to them. In some cases, the need is to focus on dangers within the organization. There is no such thing as the ideal set of organizational behaviors or management practices, except in relation to what the organization is trying to do.

5. Successful companies are those that came up with a way forward which is timely, credible, simple, and – most crucial of all – able to be readily applied. In the final analysis, organizational success comes down to implementation. The best ideas poorly executed are worthless.

Of course, organizational structure and leadership are critical. In addition to organizational structure, issues such as what mix of transactional and transformational leadership are implemented in an organization affect behavior in an organization.

Technology and Organizational Behavior

So much can be offered regarding how technology has affected OB and communications that to properly address that topic is beyond the scope of this paper. There are some very key points; however, that need to be stated.

The first is in decision-making. Typically, leadership makes all the big strategic decisions about what the company is going to do. The difference is that decision-making in the technology age is often a more collaborative process. Another facet of decision-making in many actual technology companies is they grow too fast to be managed closely from the center. Decisions, once taken centrally, are rapidly devolved to those working in the business to determine the method and manner of implementation.

The next is in internal communications. This is not a problem in the early days when the organization consists of a small group of highly motivated people who spend a lot of time in each other’s company, and who therefore automatically keep themselves and each other in the picture. However, business growth needs to be fueled by new blood. These are people who were not part of the original setup and therefore processes and systems need to be introduced to ensure that everybody is kept informed – it no longer happens naturally. For Internet businesses, the speed of growth means that the need for more formalized communication systems can kick in very quickly.

Next, the working day now lasts 24 hours. Information technology has the capacity not only to change where knowledge and power reside in the organization; it also changes time. The ‘‘working day’’ has less meaning in a global village where communication via e-mail, voicemail, and facsimile transmissions can be sent or received at any time of day or night.

Paradoxically, as the working day has expanded, so time has contracted. Companies compete on speed, using effective co-ordination of resources to reduce the time needed to develop new products, deliver orders or react to customer requests. Add to that how growth has decoupled from employment (meaning that technology often makes jobs go away and keeps companies in a permanent state of change), and one can see how this has transformed creating transparent workplaces at every organization level through giving employees a near-comprehensive view of the entire business. These technologies surrender knowledge to anyone with the requisite skills who can access the know-how.

Finally, the rise of the virtual organization formed by a cluster of interested parties to achieve a specific aim – perhaps to bring a specific product or idea to market – and then disappear when the aim has been achieved. The concept is not just a useful tactic for corporate downsizing, it also carries ideological weight. The manager who can cope is best prepared to handle the ongoing change occurring in organizations today.

Furthermore, technology affects OB when sweeping new systems are implemented. Enterprise resource planning systems aim to manage all aspects of a business including: production planning, purchasing, manufacturing, sales distribution, accounting and customer service, for example, and are complex systems that are difficult and costly to implement successfully. They influence all the most all the key players in an organization.

Edwards & Humphries (2005) offer an excellent window into what can happen in organizations when this occurs in case example regarding PowerIT, Ltd.’s attempt to implement a sweeping ERP system. They stated that:

“Although the initial perception of the team was that the chief executive officer and financial director had been committed to the project... interviews with the employees at managerial and shop floor levels indicated that there was little active involvement in, or acknowledgment of, the project by the chief executive officer and other senior managers. Therefore, at operational levels the project was not seen as a "high-priority" activity. This perception had ramifications on the way people interacted with the business development manager and related to the project. Although the business development manager had a good technical skills set, he lacked the social skills required to operate effectively in a traditional manufacturing environment. There were obvious personality clashes and conflicts between the business development manager and other managers (and hence their staff)” (p. 154).

Antagonism, conflict, and power struggles eventually ensued between and on every managerial level in the organization. A specialized team was created, an investigation launched, and finally recommendations were made that brought the situation under control for the organization. However, the important relationship between good OB and communication skills to a successful implementation of sweeping new technologies/systems should be clear.

Management Issues

Robbins (2005) defines leadership as “the ability to influence a group toward the achievement of goals” (p. 332). Robbins notes that this influence may be formal as a manager in an organization or a person may assume a leadership role simply because of the position they hold in the organization. Not all leaders are managers nor are all managers leaders.

Trait theories are theories that consider personal qualities and characteristics that differentiate leaders from non-leaders. The approach of listing leadership qualities, assumes certain traits or characteristics will tend to lead to effective leadership. Although trait theory has an intuitive appeal, difficulties may arise in proving its tenets, and opponents frequently challenge this approach. The strongest versions of trait theory see leadership characteristics as innate, and accordingly label some people as "born leaders" due to their psychological makeup.

As a result of these behavioral theories of leadership, leadership development involves identifying and measuring leadership qualities, screening potential leaders from non-leaders, then training those with potential.

Initiating structure refers to the extent to which a leader is likely to define and structure his or her role and those of subordinates in the search for goal attainment while consideration involves the extent to which a leader is likely to have job relationships characterize by mutual trust, respect for subordinate’s ideas, and regard for their feelings.

An employee-oriented leader emphasizes interpersonal relations while a production-oriented leader emphasizes the technical or task aspects of the job. A development-oriented leader is one who values experimentation, seeks new ideas, and generates and implements change. In fact, there is a managerial grid proposed that outlines 81 different leadership styles.

The Fiedler contingency model believes a key factor in leadership success is the individual’s basic leadership style. The goal is to match leaders and situations and Robbins discusses many other models in chapter eleven on how leaders can be successful and in chapter twelve discusses how effective managers must develop trusting relationships with followers and exhibit transformational leadership qualities using vision and charisma to carry out those visions.

No matter how one defines leadership, it typically involves an element of vision, except in cases of involuntary leadership. The vision provides direction to the influence process. A leader (or group of leaders) can have a vision of the future to aid them to move a group successfully towards this goal.

Differences in the mix of leadership and management can define various management styles. Some management styles tend to de-emphasize leadership. Included in this group one could include participatory management, democratic management, and collaborative management styles. Other management styles, such as authoritarian management, micro-management, and top-down management, depend more on a leader to provide direction.

Note, however, that just because an organization has no single leader giving it direction, does not mean it necessarily has weak leadership. So, in contrast to individual leadership, some organizations have adopted group leadership. In this situation, more than one person provides direction to the group. Some organizations have taken this approach in hopes of increasing creativity, reducing costs, or downsizing. Others may see the traditional leadership of a boss as costing too much in team performance.

In some situations, the maintenance of the boss becomes too expensive - either by draining the resources of the group, or by impeding the creativity within the team, even unintentionally. A common example of group leadership involves cross-functional teams. As a compromise between individual leadership and an open group, leadership structures of two or three people or entities also occur commonly.

Emotional intelligence (EI) is a predictor of leadership. The five components of EI are self-awareness, self-management, self-motivation, empathy, and social skills. These allow an individual to become a star performer. Without EI, a person can have training, a great mind, long term vision, and terrific ideas but still will not make a great leader. Robbins (2005) states that “the evidence indicates that the higher the rank of a person considered to be a star performer, the more EI capabilities surface as the reason for their effectiveness” (p. 368).

Generally, psychological research indicates that IQ is a reliable measure of cognitive capacity, and is stable over time. In the area of EI that distinction is murky. Current definitions of EQ are inconsistent about what it measures: some (such as Bradberry and Greaves 2005) say that EQ is dynamic; it can be learned or increased; whereas others (such as Mayers) say that EQ is stable. Under Mayer's view, emotional knowledge would be the level of perception and assessment that an individual has of their emotions at any given moment in time.

An understanding of power and politics within organizations is essential. How power is derived, its dependencies, bases of power, tactics and strategies, and how power functions in groups are all important to being a successful manager and leader.

And many other factors such as perception and communications must be taken into consideration as well. For example, Robbins (2005) describes the functions of communication as serving “four major functions within a group or organization: control, motivation, emotional expression, and information” (p. 299).

Communication acts to control member behavior in various ways both thru formal and informal channels and plays a role, as does power and politics, in addressing conflict and negotiation.

The most important point here is that whichever of these scenarios a manager works in; they must bring the right leadership skills to bear, appropriately and effectively, if they are to become a truly successful manager.

Conclusions

OB is a field of study interested in individuals, groups, and structures using methods such as economics, sociology, political science, anthropology, and psychology and seeks to control, predict, and explain. OB models, theories, and types are important for bringing systemization to the field.

Managers must understand OB as a discipline that underpins practical organizational activities and understand how to use the underlying technology. Also, managers need to understand the management issues involved in OB and related fields to be good managers (and leaders for example). OB plays a critical factor in both the success of an organization and a manager. The successful manager wisely incorporates what works, with respect to OB, into their managerial toolkit.

Reader’s Note:

As stated, the output of organizational behavior studies reflects contributions (inputs) from other academic disciplines. When faulty and fallacious ideologies and worldviews corrupt these disciplines resulting in contributions (inputs) that are faulty, fallacious, etc.: the output and subsequent application that depends on them is flawed.

The author may prepare a future article on organizational behavior specifically identifying key contributions (inputs) which are faulty, fallacious, etc. which became embedded in Western culture and are resulting in the escalating deterioration of behavioral outcomes over time; presently observed within Western societies, governments, institutions, and organizations.

Suitable correction and replacement of such inputs, with case examples, can be presented from a correct objective perspective of the orthodox Christian worldview, fixed in biblical truth, in which actual truth corresponds with actual reality. The article could be part of a new Christian Practical Application Series (CPAS).

The following exhibit (i.e. Exhibit 1-3) is explanatory for what the author is proposing. It is an overview of major contributions (inputs) to the study of organizational behavior:

Bibliography:

Brown, S. (2006). Myths of free trade: why American trade policy has failed. The New Press.

Bryant, S.E. (2003). The role of transformational and transactional leadership in creating, sharing and exploiting organizational knowledge. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 9, 32.

Coghlan, D. (2024). Edgar H. Schein: the artistry of a reflexive organizational scholar-practitioner. Routledge.

Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., Wesson, M. J., & Gellatly, I. R. (2016). Organizational behavior: improving performance and commitment in the workplace. McGraw Hill.

Corey, G. (2020). Theory and practice of counseling and psychotherapy (10th ed.). Brooks/Cole.

Edwards, H. M. & Humphries, L. P. (2005, October). Change management of people & technology in an ERP implementation. Journal of Cases on Information Technology. Hershey, 7, 144-162.

Fayol H. (1949). General and industrial management. Pitman.

Fletcher, I. (2011). Free trade doesn’t work: what should replace it and why (2nd ed.). Coalition for a Prosperous America.

Foreign-born workers were a record high 18.1 percent of the U.S. civilian labor force in 2022: The Economics Daily: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2023, June 16). Www.bls.gov. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2023/foreign-born-workers-were-a-record-high-18-1-percent-of-the-u-s-civilian-labor-force-in-2022.htm

French, R. (2006). Driven abroad: the outsourcing of America. RDR Books.

Gooding, D. & Lennox, J. (2018). Doing what's right: whose system of ethics is good enough? Myrtlefield House.

Gooding, D. & Lennox, J. (2020). The Bible and ethics: finding the moral foundations of the Christian faith. Myrtlefield House.

Greenberg, J. (2008). Behavior in organizations (10th ed.). Pearson.

Gunnoe, M. L. (2022). The person in psychology and Christianity: a faith-based critique of five theories of social development. IVP Academic.

Hira R., & Hira A. (2005). Outsourcing America: what's behind our national crisis and how we can reclaim American jobs. American Management Association.

Humphreys, J.H. and Einstein, W.O. (2003). Nothing new under the sun: Transformational leadership from a historical perspective. Management Decision, 41, 85-96.

Johns, G., & Saks, A. M. (2017). Organizational behavior: understanding and managing life at work (10th ed.). Pearson.

Jones, S. L. & Butman, R. E. (2011). Modern psychotherapies: a comprehensive Christian appraisal (2nd ed.). IVP Academic.

Lennox, J. (2007). God's undertaker: has science buried God? Lion Hudson.

Lennox, J. (2011). Gunning for God: why the new atheists are missing the target. Lion Hudson.

Lennox, J. (2013). Miracles: is belief in the supernatural irrational? Veritas.

Lennox, J. (2024, December 28). John Lennox: you don’t have to choose between God and science (S. Marusca, Interviewer). In Practical Wisdom.

Lighthizer, R. (2023). No trade is free: changing course, taking on China, and helping America's workers. Broadside Books.

Middleton, J. (2002). Organizational behavior. Capstone Publishing.

Organizational behavior. (2025, February 9). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Organizational_behavior&oldid=1274828771

Organizational behavior management. (2025, February 5). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Organizational_behavior_management&oldid=1274031016

Ozaralli, N. (2003). Effects of transformational leadership on empowerment and team effectiveness. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 24, 335-345.

Perkel, S. E. (2005, June). Bad leadership: what it is, how it happens, why it matters. Consulting to Management. Burlingame, 16, 59-62.

Resick, C. (2019). Journal of Organizational Behavior - Wiley Online Library. Wiley.com. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10991379

Robbins, S. P. (2005). Organizational behavior (11th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Robbins, S. P., & Judge, T. A. (2024). Organizational behavior (19th ed.). Pearson.

Roberts, P. C. (2010). How the economy was lost. AK Press.

Schaeffer, F. A. (2005). How should we then live?: the rise and decline of western thought and culture. Crossway Books.

Schein, E. H. (2017). Organizational culture and leadership (5th ed.). Wiley.

Skinner, B. F. (1999). Cumulative record: definitive edition. Xanedu.

Stern, P. M. (1992). Still the best Congress money can buy. Gateway Books.

Taylor, F. W. (1919). The principles of scientific management. Harper & Brothers.

Walumbwa, F.O., Wang, P., Lawler, J.J., and Shi, K. (2004). The role of collective efficacy in the relations between transformational leadership and work outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77, 515-531.

Wagner, J. A., & Hollenbeck, J. R. (2010). Organizational behavior: securing competitive advantage. Routledge.

Wartzman, R. (2017). The end of loyalty: the rise and fall of good jobs in America. Public Affairs.

Weber, M. (1968). Economy and society: an outline of interpretive sociology. Bedminister Press.

Wood, J. (1996). Mastering Management. Prentice Hall.

Fair Use: Copyright Disclaimer Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act in 1976; Allowance is made for "Fair Use" for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statue that might otherwise be infringing. All rights and credit go directly to its rightful owners. No copyright infringement intended.

Copyright © 2025 Paul L. Pothier. All rights reserved.