This is article nine in the Educational Business Series (EBS).

Introduction

Strategic Management “is the art and science of formulating, implementing, and evaluating cross-functional decisions that enable an organization to achieve its objectives (David & David, 2017, p. 5).

When done correctly, strategic management assists organizations with developing plans to gain competitive objectives and meet long-term objectives. Both the external environment and internal capabilities must be considered.

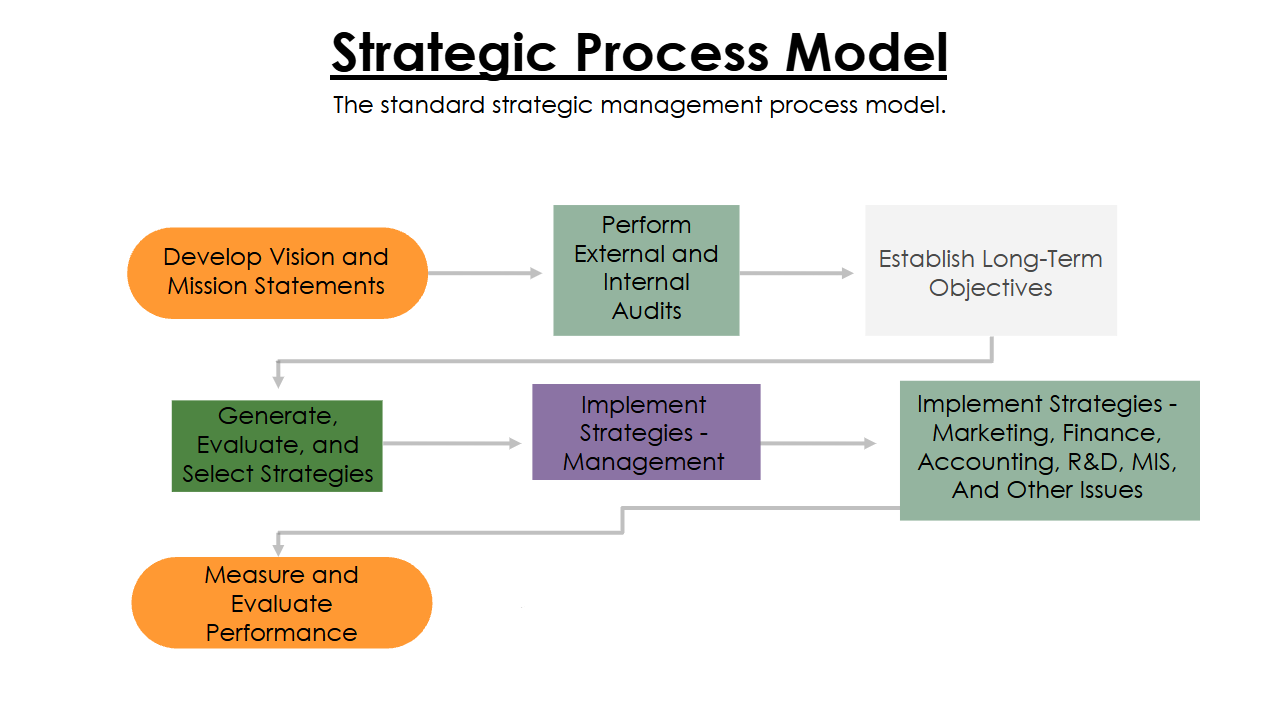

The strategic management process model outlines the strategic process and associated ratios, tools, and sub-models that are used to accomplish this.

Historical Information

Though strategic management has its earliest roots in the military and political strategies of antiquity, modern strategic management as a formal discipline first took shape in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

By the 1930s and 1940s, the work of innovators such as Frederick Taylor and Henri Fayol were improving operational efficiency and administration. By the 1950s, innovators such as Peter Drucker were promoting the benefit of early systematic goal-setting processes.

“The 1960s marked the birth of strategic management as a distinct field, driven by the growth of large corporations and the need for systematic planning in an increasingly complex business landscape” (xAI, Grok 3, 2025).

Alfred Chandler published Strategy and Structure in 1965 which argued that the structure of an organization should follow its strategic goals.

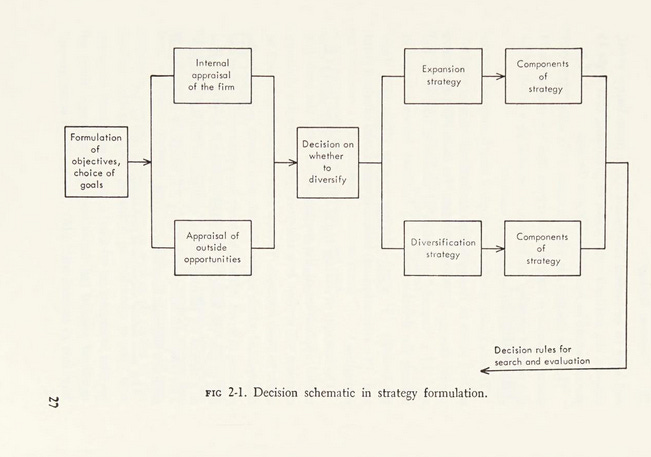

Igor Ansoff, often referred to as the father of strategic management, published Corporate strategy; an analytic approach to business policy for growth and expansion in 1965 which introduced the first modern corporate strategy model and the Ansoff Matrix, a tool for analyzing growth strategies. The following image, from page 27, articulates his original vision of strategy formulation decision-making.

In the 1970s, the Boston Consulting Group developed their own growth-share matrix to help organizations allocate resources strategically. It was also in the 1970s that analytical tools such as the SWOT analysis (which analyzes strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) became widely used.

During the 1980s and 1990s, strategic management matured emphasizing competition and internal capabilities. The Strategic Management Society formed in 1981 while innovators such as Michael Porter introduced the Five Forces model which analyzes industry competitiveness; and Jay Barney championed the Resource-Based View (RBV) which assists organizations in using their internal resources and capabilities to gain competitive advantages emerged.

Further advances include the concept of core competencies by C. K. Prahalad and Gary Hamel to leverage unique strengths in strategy management.

From the turn of the new millennium to the present, modern developments emerged encouraging flexibility and responsiveness introducing topics such as dynamic capabilities which help organizations adapt and innovate; a greater emphasis placed on globalization and technology; as well as integrating environmental and social considerations.

The Strategic Management Process Model

As stated in the introduction, strategic management formulates, implements, and evaluates cross-functional decisions to enable organizations to achieve their objectives. This is accomplished using a strategic management process which “consists of three stages: strategy formulation, strategy implementation, and strategy evaluation (David & David, 2017, p. 5).

David & David (2017) defines strategy formulation, strategy implementation, and strategy evaluation as follows:

I. “Strategy formulation: Stage 1 in the strategic management process; includes developing a vision/mission, identifying an organization’s external opportunities/threats, determining internal strengths/weaknesses, establishing long-term objectives, generating alternative strategies, and choosing particular strategies to pursue.

II. Strategy implementation: Stage 2 of the strategic management process. Activities include establishing annual objectives, devising policies, motivating employees, allocating resources, developing a strategy-supportive culture, creating an effective organizational structure, redirecting marketing efforts, preparing budgets, developing and utilizing information systems, and linking employee compensation to organizational performance.

III. Strategy evaluation: Stage 3 in the strategic management process. The three fundamental strategy evaluation activities are (1) review external and internal factors that are the bases for current strategies, (2) measure performance, and (3) take corrective actions; strategies need to be evaluated regularly because external and internal factors constantly change” (p. 634).

These three stages are incorporated into the standard strategic management process model and implemented around the world by governments and organizations, in diverse ways.

Review the following flowchart of the strategic process model and note each objective.

Each objective in the strategic process model is introduced with the most widely used tools that correspond with each objective in the strategic process:

I. Vision and mission statements.

1. Vision statement: A vision statement should answer the question of what an entity is to become. It is a purposeful brief declaration articulating an entity’s aspirations and desired future state. The vision statement should align with the entity’s core values and provide direction for strategic planning and decision-making.

2. Mission statement: A mission statement should declare an entity’s reason for existing. It should define an entity’s purpose, core activities, and primary objectives briefly articulating what the entity does and how the entity accomplishes that. The mission statement should align with the entity’s core values and provide direction for strategic planning and decision-making.

II. External and internal audits.

1. External audit: “The purpose of an external audit is to develop a finite list of opportunities that could benefit a firm as well as threats that should be avoided.” The audit should “identify key variables that offer actionable responses” (David & David, 2017, p. 61).

Multiple dimensions of an entity's external environment are assessed. Frameworks like PESTEL (Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, Legal) in conjunction with tools such as SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) are employed to discover the key variables so that actionable responses can be formulated. The external audit process is structured and involves data collection, environmental scanning, competitive analysis, synthesis and interpretation, reporting and integration, and action planning (e.g. product development, marketing strategy, resource allocation, mergers and acquisitions, risk management, etc.) (xAI, Grok 3, 2025).

Common tools used in the external audit include SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats), competitive analysis, Porter’s five-forces model, the competitive profile matrix (CPM), industry analysis, and the external factor evaluation (EFE) matrix.

2. Internal audit: Entities have strengths and weaknesses in functional areas. The internal audit assesses them with an eye toward enhancing governance, risk management, and operational efficiency. “Internal strengths and weaknesses, coupled with external opportunities and threats and clear vision and mission statements, provide the basis for establishing objectives and strategies. Objectives and strategies are established with the intention of capitalizing on internal strengths and overcoming weaknesses… the process of performing an internal audit closely parallels the process of performing an external audit” (David & David, 2017, p. 90-92).

Key components of a successful strategic management internal audit include developing an internal audit strategy, taking a risk-based approach, gaining stakeholder engagement, integrating with organizational strategy, assessing and leveraging technology and innovation, ensuring a skilled audit team is employed, and evolving with organizational and regulatory changes as they occur (xAI, Grok 3, 2025).

Key internal audit techniques include analytical procedures, control testing, substantive testing, performance audits, strategic audits, root cause analysis, and the documentation of processes by maintaining a performance management manual to outline audit processes, roles, and improvement tools (xAI, Grok 3, 2025).

The areas to audit include strategy and culture, management, marketing, finance and accounting, production/operations, research and development, management information systems, and value chain analysis (David & David, 2017, pp. 92-121).

Common tools used in the internal audit include SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats), computing key financial ratios. (see Table 4.4 in David, 2017, p. 106 for ratio calculations), liquidity ratios, leverage ratios, activity ratios, profitability ratios, growth ratios, the internal factor evaluation (IFE) Matrix, etc.

III. Long-term objectives: “Long-term objectives represent the results expected from pursuing certain strategies. Strategies represent the actions to be taken to accomplish long-term objectives. The time frame for objectives and strategies should be consistent, usually from 2 to 5 years… objectives should be quantitative, measurable, realistic, understandable, challenging, hierarchical, obtainable, and congruent among organizational units” (David & David, 2017, p. 130-131).

Financial objectives deal with revenues, earnings, dividends, profit margins, return on investment, earnings per share, stock price, cash flow, etc. Strategic objectives deal with market share, on-time delivery, design-to-market, costs, quality, geographic coverage, technology, leadership, development, marketing, etc. Trade-offs must be assessed and determined as they arise. Integration strategies include vertical, horizontal, forward, and backward. Strategies may include intensive strategies (e.g. market penetration, market development, and product development); diversification strategies (e.g. related diversification and unrelated diversification); defensive strategies (e.g. retrenchment, divestiture, and liquidation). The tactics and means for facilitating and achieving strategies must be carefully considered (David & David, 2017, pp. 131-158).

Common tools used in long-term objective strategic planning include the balanced score card and Porter’s five generic strategies.

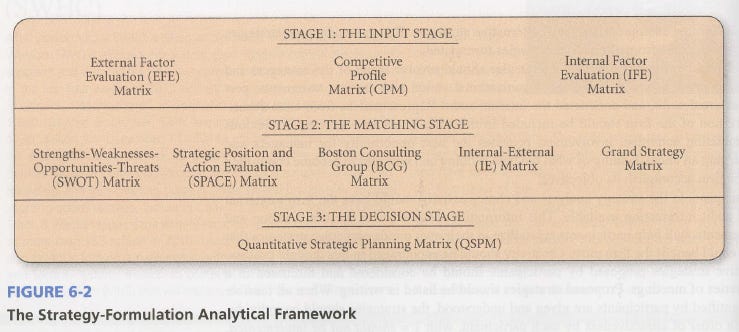

IV. Generate, evaluate, and select strategies: “Strategy analysis and choice largely involve making subjective decisions based on objective information... strategy analysis and choice seek to determine alternative courses of action that could best enable the firm to achieve its mission and objectives.” (David & David, 2017, p. 168).

All participants in the strategy analysis and choice activity should have the firm’s external and internal audit information, vision and mission statements, and relevant information available to them as they engage in analyzing strategies.

Review the following Strategy-Formulation Analytical Framework from (David & David, 2017, p. 170) and note each stage with its associated steps.

Stage 1 (input stage): EFE Matrix, IFE Matrix, and CPM.

Stage 2 (matching stage): SWOT Matrix, SPACE Matrix, BCG Matrix, IE Matrix, and GSM.

Stage 3 (decision stage): QSPM.

Other considerations involve organizational cultural aspects, internal politics, and governance issues. The tools listed in the three stages can enhance the quality of strategic decisions.

V. Implementing strategies (part 1). Management, operations, and human resources are all involved in implementing strategies. “Implementing strategy affects an organization from top to bottom, including all of the functional and divisional areas…” (David & David, 2017, p. 206).

As strategy implementation is initiated the focus becomes action, responsibility, efficiency, operations, motivation and leadership, coordination, in a people-oriented manner. Policies and structure are used. Evaluations are performed to see how well things adhere with strategy formulation, how well things are going, and what problems need to be resolved.

V. Implementing strategies (part 2). Marketing, finance/accounting, research and development, and management information systems are central to successful strategy implementation. Products and services must be marketed effectively with adequate working capital available. A host of issues and methods (product positioning mapping, earnings per share/earnings before interest and taxes (EBP/EBIT) analysis, etc.) are involved as is the need for cooperation among all functional and divisional managers.

VI. Measure and evaluate performance. “The best formulated and best implemented strategies become obsolete as a firm’s external and internal environments change. It is essential, therefore, that strategists systematically review, evaluate, and control the execution of strategies… erroneous strategic decisions can inflict severe penalties and can be exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, to reverse. Therefore, most strategists agree that strategy evaluation is vital to an organization’s well-being; timely evaluations can alert management to problems or potential problems before a situation becomes critical” (David & David, 2017, p. 280).

Strategy evaluation consists of three activities:

1. Analyze the basis of the strategy.

2. Compare expected results with actual results.

3. Take corrective action as needed.

Common tools used in strategy evaluation include the balanced score card, auditing, etc.

Other Considerations

These include the rule of law, business ethics, social responsibility, environmental concerns, sociocultural norms, and global and international issues.

As previously stated, when done correctly strategic management assists organizations with developing plans to gain competitive objectives and meet long-term objectives.

For those looking to gain a much more thorough and in-depth understanding, the later editions (16th edition and above) of David & David’s Strategic Management: A Competitive Advantage Approach (Concepts & Cases) are highly recommended. These editions also take the readers through each step of each objective in the strategic process that has been introduced here, in conjunction with the usage of the most common tools associated with each objective. Additionally, instructions for preparing and presenting strategic management cases (i.e. strategic management case analysis and presentation) are provided, with real world examples illustrated, and finally completed strategic management sample cases included.

Conclusion

“The history of strategic management reflects a journey from early management theories and military strategy to a formalized discipline in the 1960s and 1970s, with significant advancements in the 1980s through figures like Porter. Over time, it has evolved to address the complexities of modern business, incorporating insights from competition, resources, and innovation. This ongoing evolution ensures its relevance in guiding organizations through an ever-changing landscape” (xAI, Grok 3, 2025).

Bibliography:

2024 Global Internal Audit Standards. (2025). The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA). [Standard 9.2]. https://www.theiia.org/en/standards/2024-standards/global-internal-audit-standards/

Almaney, A. J. (1998). Strategic management: the process of gaining a competitive advantage. Stipes Publishing.

Analoui, F. & Karami, A. (2003). Strategic management in small and medium enterprises. Thomson.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Barney, J. B. (2007). Resource-based theory: creating and sustaining competitive advantage. Oxford University Press.

Chandler, A. D. (1962). Strategy and structure: chapters in the history of the industrial enterprise. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press.

David, F. R. (2005). Strategic management: concepts and cases (10th edition). Pearson.

David, F. R. & David, F. R. (2017). Strategic management: concepts and cases (16th edition). Pearson.

David, F. R., David, F. R., & David, M. E. (2021). Strategy Club. https://www.strategyclub.com

Fayol H. (1949). General and industrial management. Pitman.

Gratton, P. (2025, March 28). Porter’s 5 Forces explained and how to use the model. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/p/porter.asp

Grunig, R. & Kuhn, R. (2001). Process-based strategic planning. Springer.

Hamel, G. & Prahalad, C. K. (1996). Competing for the future. Harvard Business School Press.

Hayes, A. (2024, June 25). Understanding the BCG Growth Share Matrix and How to Use It. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/b/bcg.asp

Igor, A. H. (1965). Corporate strategy; an analytic approach to business policy for growth and expansion. McGraw-Hill.

Igor, A. H. (1987). Corporate Strategy (revised edition). Penguin Books.

Igor, A. H., McDonnell, E., & Beach, S. (1990). Implanting Strategic Management (2nd edition). Prentice Hall.

Jauch, L. R. & Glueck W. F. (1988). Business policy and strategic management. McGraw-Hill.

Macmillan, H. & Tampoe, M. (2000). Strategic management: process, content, and implementation. Oxford University Press.

Mckeown, M. (2012). The strategy book. Pearson.

Pearce II, J. A. & Robinson, R. B. (2003). Strategic management: formulation, implementation, and control (eighth edition). McGraw-Hill.

Rainey, D. L. (2010). Enterprise-wide strategic management: achieving sustainable success through leadership, strategies, and value creation. Cambridge University Press.

Taylor, F. W. (1919). The principles of scientific management. Harper & Brothers.

xAI. (2025). Grok (version 3) [DeepSearch]. https://grok.com/

Fair Use: Copyright Disclaimer Under Section 107 of the Copyright Act in 1976; Allowance is made for "Fair Use" for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statue that might otherwise be infringing. All rights and credit go directly to its rightful owners. No copyright infringement intended.

Copyright © 2025 Paul L. Pothier. All rights reserved.